I recently decided to delve a little deeper into Kubernetes by building my own multitenant platform using Capsule.

This isn’t meant as a tutorial really, I just want to document my learning so far.

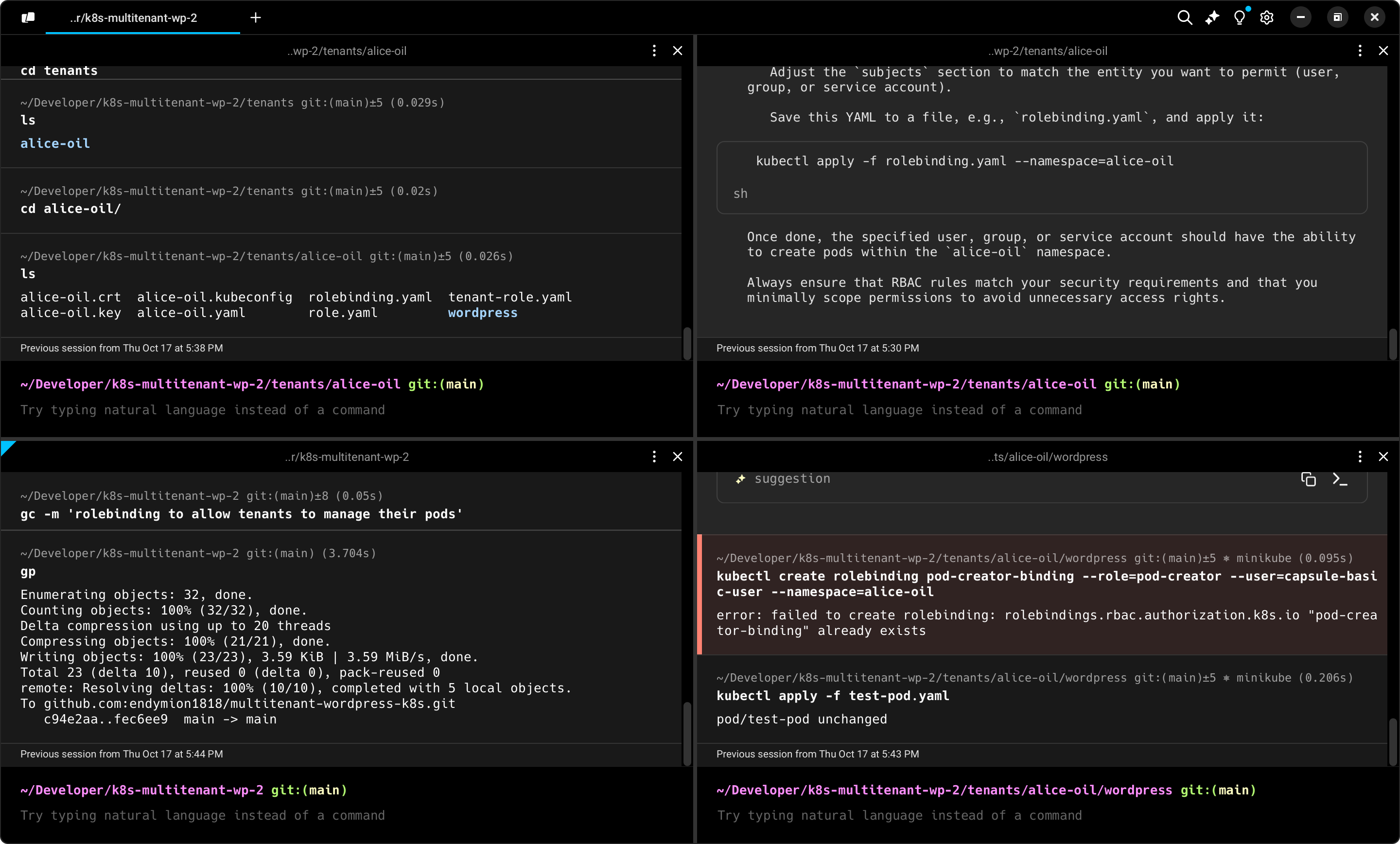

Firstly, I must say that my explorations of Kubernetes and friends would have been a lot more challenging if if hadn’t been for Warp, a terminal emulator that has great multiplexing and a built-in AI trained on the publicly available docs of relevant tools.

I set myself the following key requirements:

- To utilise baremetal or virtual servers, not tied to one service or hosting company

- To isolate each environment so they can’t accidentally visit each others’ sites

- To facilitate easy creation, deletion and “pausing” of the environment

- To use a custom domain for each

That last one is a bit more of a challenge since I am not all that familiar with load balancers yet, but we’ll get there…

Reproducability

I had my own set of requirements to fulfil alongside these that I thought would help, most of these revolve around reproducability.

I wanted to be able to destroy and spin up new environments easily. That meant using the Helm package manager, Helmfile. With this tool I can declare the system I want, which would also help to roll the system back to a previous state more easily.

I also wanted the environment to be built with Infrastructure-as-code. A machine can easily become corrupted or attacked. For these reasons, I am much more inclined towards thinking about them as disposable tools than precious investments.

So here’s the Helmfile I cam up with (with a little help from Warp):

repositories:

- name: clastix

url: https://clastix.github.io/charts

releases:

- name: capsule

namespace: capsule-system

chart: clastix/capsule

version: 0.4.6

values:

- capsule:

config:

forceTenantPrefix: false

protectedNamespaceRegex: "^(kube-system|kube-public|kube-node-lease|kube-kube-.*|default|capsule-system)$"

protectedNamespaceLabels: []

enableTLS: true

logLevel: info

ingress:

enabled: false

hostName: capsule.local

annotations: {}

tls:

enabled: true

secretName: ""

resources:

requests:

cpu: "100m"

memory: "128Mi"

limits:

cpu: "200m"

memory: "256Mi"

nodeSelector: {}

tolerations: []

additionalLabels: {}

additionalAnnotations: {}

repositories:I had a voucher from Linode (Linode is quickly being rebranded as Akamai Connected Cloud), which I was grateful for since that helped me get familiar with the difference between nodes and pods: nodes are external resources such as my Linode VMs, pods are internal resources. The number of nodes you have depends on how many VMs you have (on Linode at least, one will be a controller node from which to manage the others).

However I was afraid of running out of trial credits, so I also deployed this environment locally using Minikube. I have to say, this is a great tool for trialling software locally. It deploys it’s own VM (which shows up in VirtManager on Linux), and it also creates the Kubeconfig for you automatically.

So I guess I’d better explain Kubeconfig.

How to manage Kubernetes

Kubernetes is the thing that manages your pods. To manage Kubernetes, you need Kubeconfig, a command-line tool that you can use to authenticate yourself and apply configuration to your Kubernetes namespace.

A namespace is a group of resources. In my system, the main namespace is minikube, then there’s my Capsule namespace which manages resources for my multitenant system. And of course, each of those tenants has it’s own namespace too.

You can find out what namespaces you have by running the following:

kubectl get namespacesEach time you want to change a resource you have to load the correct namespace, this is usually a switch or flag on the command line like

kubectl apply -f ./values.yaml --namespace=capsule-system

Or like this

kubectl apply -f ./values.yaml -n capsule-systemThis is telling Kubectl to apply the values from the file (-f) that follows to the namespace (-n) that follows.

As you can imagine this gets a little confusing because you can easily forget which namespace you’re in. Especially when I was setting up my first tenant and was trying to run two kubectl configurations in one terminal session. Yeah don’t try that.

To find out what user you are you can run

kubectl config view --minifyThe Capsule system

What I liked about Capsule is that it has strict namespacing. At first I tried to call the Capsule system something else, and that got me in a tangled mess. It seems you need to call it “capsule-system” or else it doesn’t work. But that helped me because I could more easily see the distinction between other namespaces (I also tried to spin up a Kubernetes dashboard).

It also, like Kubernetes does natively, uses RBAC (role-based access control). This is similar to what you see in AWS: you need to create a user first, then assign them a role, and the permissions they need live inside that role, not with the actual user.

This is a useful abstraction because if your user is compromised you can withdraw their permissions which will preserve the resources and the permissions they need to function.

But it does take some getting used to. If your kubectl is set to use a tenant, they won’t be able to do a lot unless you first load the capsule system user which has all the necessary permissions to grant those to your users.

kubectl get rolebindings,clusterrolebindings --all-namespaces -o wideThis is useful for finding out what permissions each user has.

You can imagine this can get a bit frustrating, especially if you’re just trying to work this out.

I like to drop myself in the deep end like that.

However I did get more than a little frustrated that this whole thing is only partially declarative.

What I mean by that is that you have to perform the following steps to do anything significant:

- Alter your YAML files to modify permissions

- Apply the config

- Check it worked

- Undo your alterations if it didn’t

- Apply the config to roll it back

This gets tedious and more than once I forgot to un-apply my changes and therefore had to unpick things a few times.

For me it was like having committed to a remote Git branch and then only being able to see the effects on a hosted environment. It’s a rather wide feedback loop that I want to shorten.

There’s not a lot of documentation for multi-tenancy systems. I guess if you’re building one you’re not exactly going to shout it from the rooftops.

Another approach

I did find this documentation from another IAC platform I really like, Pulumi. It’s been AI generated but might be a good starting point. I like the fact that I can programatically declare my namespace and tenants in one file:

import * as k8s from "@pulumi/kubernetes";

// Create a Kubernetes cluster using the preferred cloud provider.

// This is an abstract example; specifics would depend on the cloud provider in use.

const cluster = new k8s.Cluster("multi-tenant-cluster", {

// Configure the cluster settings here.

// For example, on AWS you would set the version and node type,

// and the Pulumi AWSX library would provision an EKS cluster for you.

});

// Configure Kubernetes provider to use the generated kubeconfig from the cluster above.

const provider = new k8s.Provider("k8s-provider", {

kubeconfig: cluster.kubeconfig,

});

// Create namespaces for each tenant.

const tenantA = new k8s.core.v1.Namespace("tenant-a", {}, { provider });

const tenantB = new k8s.core.v1.Namespace("tenant-b", {}, { provider });

// Now we might apply a Kuma installation to our cluster

// Note: Specifics would vary based on your use case and would likely involve

// custom configurations, which are beyond the scope of this program.

// We assume that we have a definition file `kuma-control-plane.yaml` that contains

// the resources to set up Kuma, including a Namespace, Deployments, Services, etc.

const kuma = new k8s.yaml.ConfigGroup("kuma", {

files: ["kuma-control-plane.yaml"],

}, { provider });

// Export the kubeconfig to access your cluster.

export const kubeconfig = cluster.kubeconfig;And yes, that’s infrastructure as code with TypeScript. A significant abstraction but one I can get behind.

This is far from complete of course, there’s a long list of things to set up besides this, which since there’s no copyright on AI generated docs I can paste here directly in case it’s taken down:

- Define a ClusterRole and associated ClusterRoleBinding (or RoleBinding in each namespace) for each tenant.

- Set up network policies to restrict traffic flow between the tenants.

- Install Kuma following its documentation, tailoring the setup to your cluster’s network configuration and the permissions required.

- Ensure that your Kuma setup works with your multi-tenancy setup, e.g., by making sure that Kuma’s control plane respects namespace boundaries and RBAC rules.

I think I’m going to try this again next time the kids are in the pool.

Next steps

I’ve got a long way to go still: I want to automate the creation of a very specific application setup for my tenants, and each of them will need to have an ingress, I know nothing about how load balancers work yet so I’m going to have to figure that out.

But this has been an enjoyable learning exercise.