This past year I’ve been involved in replatforming our media player to use media-chrome from Mux instead of JWPlayer. Here’s how that went.

I hate JWPlayer with a passion. Everything that should be easy about it causes us as a development team headaches every day. Here’s an example:

let numberOfTimesChecked = 0;

function doSomething() {

setTimeout(() => {

if(typeof jwplayer === 'function' && jwplayer().hasOwnProperty("play")) {

doSomething();

} else {

numberOfTimesChecked += 1;

return;

}

}, 500)

}If you’re any kind of javascript developer you’re screaming internally now, aren’t you?

This function uses recursion to fire the function again continually every half a second because there’s no way to verify that JWPlayer is ready before you call it.

JWPlayer makes API calls to their CDN (another reason we’re moving away: we have corporate clients who proactively block code delivery CDNs). These calls check whether the token we provide is valid and load extra code that’s not included in the bundle (hls.js is loaded from their domain using this method. Don’t ask me whether the hls.js code has been modified, I have no idea).

Yet, jwplayer() provides no asynchronous API. Not only that, there’s a significant delay between jwplayer() being ready, and its child functions being ready, as you can see above, jwplayer().play() might not be defined when we call it.

This is stupid and is causing us to write spaghetti code to mitigate it’s … let’s call them idiosyncrasies … and I am still not sure how many users we’re letting down because of that.

So, good riddance JWPlayer.

A better way

If you’re having similar struggles, I heartily suggest you check out Media Chrome from the Mux team. This comprehensive suite of Web Components provides a lot more functionality which you can build on top of the native <video> element. They even have elements for streaming video. We use their Mux Player for decoding audio and video streams served from their platform.

I really love that you can write a simple lines of JavaScript once you’ve done npm install media-chrome:

import 'media-chrome';And you can do the rest in HTML:

<media-controller>

<video

slot="media"

src="https://stream.mux.com/DS00Spx1CV902MCtPj5WknGlR102V5HFkDe/high.mp4"

></video>

</media-controller>The slot directive tells the <media-controller> element you want to render this <video> element in the media slot.

There are other slots for things like icons, poster images, and many other fancy things.

If you’re looking for a quick implementation you can run with, I’d recommend taking a look at their website https://player.style, where you can copy and paste a theme straight into your HTML.

Of course, our situation is a bit different in that we have to provide an API for our clients to use as well as integrations for our trackers to ensure qualifications can be achieved, and settings that are publicly available to customise the player.

We also have live events as well as podcast content to think about.

This code had so many moving parts and integrations that it’s honestly a bit dizzying thinking about it all.

But honestly we started with the basic idea that we wanted it to be super easy for people to use. We wanted them to load the script and add as few lines to the page as possible.

I think we’ve achieved that, the basic implementation is

<my-media-player

token="player-token"

>

</my-media-player>Along with the script tag, that’s the basic API.

I love the fact that this is native HTML. It hides so much complexity that the average user just doesn’t need to think about.

In the first instance we didn’t want the player to fail silently when that’s in our control. As long as they have included the JS, We have to provide some UI for occasions where the video can’t be resolved.

This card shows when the provided token can’t be resolved to a specific video.

There are other notable visual differences when a livestream is playing. Specifically this changes whether they can do things like seek or otherwise skip segments of the video:

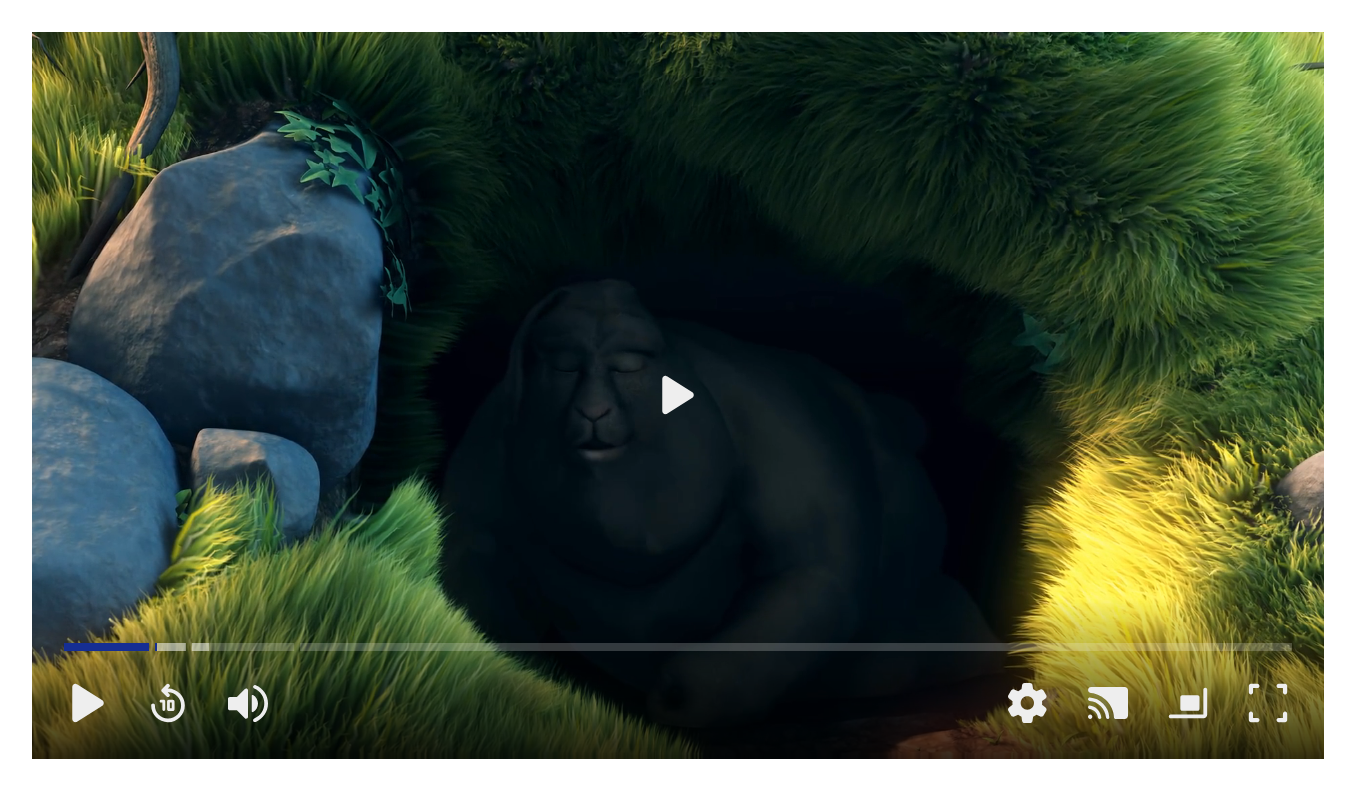

Otherwise the chrome looks like this for a video:

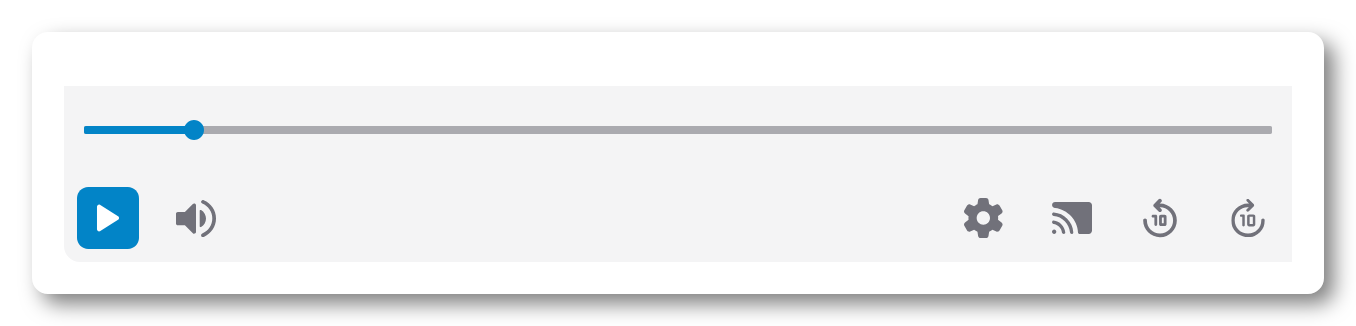

And this for audio:

There’s a huge amount of customisation available, both in what the user can provide when they instantiate the player, and in what they set up on the backend interface for options etc.

For example, they might want to show some custom branding for their channel, so the player controls will adopt their custom colour. They can add a custom button into the player. They can allow or block downloads.

Mux elements are very well thought out

I really admire how thoughtful the team has been about making this player as adaptable as it can be.

Just about all of their individual elements that make up this suite have a <slot name="icon"> so that you can override their default icons with a simple SVG element.

They also provide a huge range of CSS variables, which allow you to customise a lot of the internal CSS:

:host {

--media-font-size: 24rem;

--media-range-thumb-background: red;

}These cascade down, so as here if you do this in your :host {} block, all elements will adopt them.

Honestly, this is fantastic. A lot of the CSS is hidden in the shadow DOM, but honestly I don’t want access to all of the internals. I’ve build this complex player without being restricted by that.

Events

We also provide an API so that users can send events into the player. For example, once you’ve added the HTML code you can do:

const player = document.querySelector('media-manager-player')

player?.addEventListener('play', () => {

player.dispatchEvent(new CustomEvent('pause'))

})This is a totally contrived example but when a play even is detected we can pause it, or do any one of a number of events.

But there was one I found particularly tricky: chapters.

The use case here is that we need to expose the content of the chapters to users. We use this internally to inform users of how many chapters they need to watch before they can take a quiz which will enable them to get points towards their accreditation.

But the Mux stuff is so straightforward that it handled the chapters content for me.

<my-video-player>

<mux-video>

<track type="chapters" url="https://path/to/my/chapters.VTT">

</mux-video>

</my-video-player>Once you pass a VTT file to mux-video it fetches it and parses it to provide a chapters menu. However it doesn’t expose that content in a way I can further transform or pass back outside of the player.

So I implemented our own solution:

myPlayer.dispatchEvent(new CustomEvent('getchapters'))

myPlayer.addEventListener('chaptersdataupdated', (event) => {

console.log(event.detail) // JSON string of chapters

})Internally, this fetches the chapters, parses the VTT file and fires off the event. This means average users aren’t burdened with the extra wait time of fetching the chapters a second time as the player instantiates.

This project hasn’t been without it’s pitfalls and struggles especially since it’s been in development for around a year, so significant (and very positive) upgrades needed to me merged in.

We also found it a challenge to ensure that the code was as well tested as it can be. This is hard because most test runners assume components are instantiated in JS after the real DOM has loaded, and in this case that isn’t true. I’ve come up with a solution, and Storybook’s support has got a lot better in it’s latest release. But there are still significant gaps.

You can find a full write up on the testing situation here.

However I’m so pleased to have stumbled across the media-chrome project, and to have in that time also got to grips with native Web Components.

And yes, I did a case study for integration with Vue, React 17 and 18, and with Svelte, and the player rendered fine in all of them.